Saudi Arabia, which for many years now has been at the top of the executioner states in the world, seems to have finally taken a different path thanks to a reform on the death penalty that is supposed to guide the Kingdom towards that long-awaited modernisation proclaimed by King Salman. On 28 April 2020, the Saudi Government announced that anyone convicted of a crime that took place while they were under the age of 18 will now face a maximum punishment of ten years in juvenile detention and not the death penalty. The abolition of capital punishment for minors is one of the most important decisions for a country that has never stood out for respect of human rights; however, there are some loopholes in the reform that make it a partial revision rather than a step towards the total end of the use of the death penalty within the country.

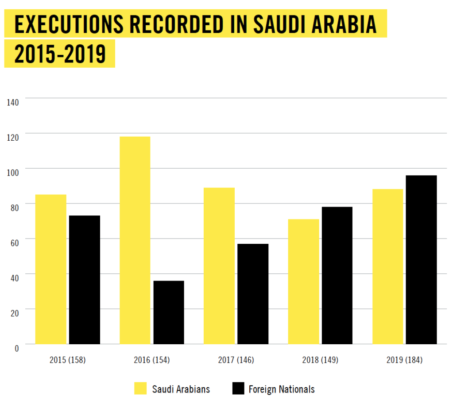

In April 2018, the Saudi Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman proclaimed the intention of the regime to minimise the application of the death penalty by reducing the number of crimes punishable by it. However, since then, the number of executions has continued to rise, from 149 in 2018 to 184 in 2019, the highest number recorded in the country in the last six years and the second in the Gulf region after Iran, showing no intention of stopping this practice. On 23 April 2019, the government proceeded with the mass execution of 37 men, 32 of whom belonged to the country’s Shiite minority. At least six of them were minors: Mohammad Saeed Al-Skafi, Salman Amin Alkoraysh, Mojtaba AlSowaiket, Abdullah Salman AlSoraih, Abdulaziz Hassan Al-Sahwi, and Abdulkarim AlHawaj.

Among the most striking cases is that of the request for the death sentence against Murtaja Qureiris; arrested at 13, he was accused of a series of crimes, some of which were committed when he was only 10 years old. He was charged with participating in demonstrations against the government, joining a terrorist organisation, launching Molotov cocktails against a police station, and using firearms against security forces. After an international pressure campaign, the prosecutor decided to spare his life and sentenced him to 12 years in prison instead.

There are no specific data on how many minors have been executed in the past years but what appears is that many of those executed did not face serious charges, including participation in anti-regime demonstrations as well as involvement in the spread of Shia Islam. In fact, in Saudi Arabia, capital punishment can be issued for a wide range of crimes, including murder, drug offences, apostasy, witchcraft, and terrorist-related crimes; and often it occurs in gravely unfair or deeply imperfect trials where the defendant had no legal representation.

Thus, the government’s announcement to abolish capital punishment for people who committed crimes when they were minors could seem like a turning point, but it is only a small step forward along the journey towards the protection of the fundamental right to life. According to the Royal Order, there are some exceptions to the new law, such as qisas and hudud offences in Shari’a law, which enables prosecutors to seek death sentences against children. By leaving them out, Saudi Arabia violates its international human rights obligations under the Convention for the Rights of the Child, which strictly prohibits the use of the death penalty against people under the age of 18.

In addition, the new regulation seems also to exclude those convicted on terrorism-related offences. In these regards, it is not yet clear how minors would be sentenced if tried under this law. What is clear is that these exceptions will have a great impact in particular due to the improper use of the anti-terrorism law which, through broad and vague definitions of the words “terrorism” and “terrorist crime”, criminalizes a series of peaceful expressions which have no relation to terrorism, but which are considered by the authorities as a danger to national unity or undermining the reputation or position of the country.

This was the case of Ali al-Nimr, Abdullah al-Zaher, and Dawood al-Marhoon, three juvenile offenders sentenced to capital punishment at the end of sham trials performed by the special anti-terrorism court. They were arrested in 2012, when they were 17, 16, and 17 respectively, for participating in anti-government protests in the Eastern Province, where discrimination against the Shi’ite community is commonplace. For the three of them and many others like them, the new law will not apply. Currently, there are 13 people facing a death sentence for terrorist offences related to participation in pro-democracy demonstrations committed when they were minors. In their case, the death penalty remains admissible, in spite of their age.

Only in 2019, 55 people were executed on charges of murder (qisas) and 37 of terrorist-related crimes. These numbers clearly show how the new law will not have a significant impact on the reduction of capital punishment convictions. Saudi Arabia continues to claim the seriousness of its human rights reforms, however, if that is the case, it needs to fully abolish the death penalty for minors; this time without any ifs or buts.